Street art: ephemerality challenging the sanction of permanence

In 2010 the Brumby government asked Heritage Victoria to undertake a study assessing the heritage value of culturally significant street art in Melbourne, as well as identifying key street art areas. The Heritage Council of Victoria was to provide the advice on how Melbourne’s street art can be appropriately recognised. This was in response to the deliberate destruction of British street artist Banksy’s work the ‘Little Diver’ in Cocker Alley and the accidental removal of another stencil work. The Planning Minister at the time Simon Madden said “we must look at what can be done to preserve this important part of our artistic and cultural heritage.” No report was ever made public by the Heritage Council.

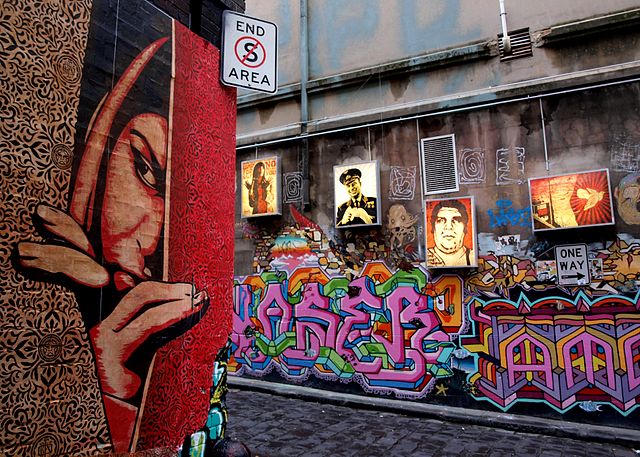

Definitions are slippery but in its broadest sense we can say that street art is any art developed in public spaces. The term can include traditional graffiti artwork, as well as stencil graffiti, sticker art, wheatpasting and street poster art, video projection, art intervention, guerrilla art, flash mobbing and street installations.

‘Graffiti’ is defined locally in the Graffiti Prevention Act (2007) as any form of writing, drawing, marking, scratching or otherwise defacing property by any means so that the defacement is not readily removable by wiping with a dry cloth. Some graffiti is legal (for example, a mural painted by street artists at the express invitation of a council), but mostly it involves markings applied to a surface without the property owner’s consent.

In 2004 the National Trust in Victoria developed a Graffiti Policy Statement acknowledging that graffiti on historic buildings is detracting, and cleaning it from masonry surfaces can result in damage and that graffiti in such places be strongly discouraged. However it also understood that some forms of street art had social significance and should be recorded and protected.

Messages scratched on walls have been part of urban life for centuries, probably well before those found on the walls of Pompeii, which date from the 1st century AD. The late 20th century however saw an explosion in the amount found on walls and objects in public places. These ranged from graffiti (political slogans, messages of love or hate, and names or signatures known as tags) to street art (painted scenes, community art, and professional artists using the style and the medium to express ideas).

Jane Eckett, from the School of Culture and Communication at the University of Melbourne, and a member of the Trust’s Public Art Committee, says ‘Street art is no longer confined to spray paint on walls. Artists have embraced a stimulating wide range of techniques, including stencils and pasteups. One of my favourite Melbourne street artists, who signs her work ‘Be Free’, is known for her use of collaged elements.”

In recent years shop and bar owners have encouraged, or even commissioned graffiti art for their walls, albeit sometimes to try to detract taggers. The City of Melbourne has for some time been actively promoting Melbourne’s street art, recognizing that it contributes to Melbourne’s international reputation for vibrant cultural diversity and appeals to local and overseas visitors. The City has funded various programs including Graffiti Mentoring and Adopt A Wall programs.

In heritage terms, the issues around transient public art are quite different to those around heritage places, buildings and objects. Eckett says: “Street art is largely premised on the idea of ephemerality. I think all street artists are aware that their creations might be painted over, or that the wall they’ve used may be pulled down, but this inherent transience is part of street art’s appeal. The effort, imagination, and skill deployed – usually for no financial benefit – are a sort of defiant gesture in the face of institutions that value and officially sanction permanence and historical longevity.”

The National Trust is of course one of those institutions that has sanctioned permanence through its classification process. Classification defines a tangible place or object for its historic, aesthetic or social significance: a place or object is significant or it is not. In 2006 Mark Halsey and Alison Young contended that graffiti “cannot be adequately described in binary terms of good versus bad art, criminal versus legal, creative versus destructive but instead as “something intangible, something which resists attempts to capture its meaning”. The problem of attempting a distinction between ‘good’ street art and ‘bad’ graffiti has been addressed by Lachlan MacDowell in his recent book on Keith Haring:

“In both public discussion and policy responses a recurring distinction is made between ‘good’ and ‘bad’ graffiti. Accordingly ‘bad’ graffiti is exemplified by ‘tagging – illegible scrawls seen to have no clear meaning or aesthetic values – while ‘good’ graffiti typically refers to colourful artworks with features that are recognisable to the general public, such as human faces and figures, animals and reworked images for popular culture. While this is a convenient distinction that equates individual preferences with broader aesthetic (or moral) values, in practice it is impossible to draw clear distinctions between these categories. Discussions of the value of Haring’s work, with its accessible styles and childlike images, become easily drawn into these kinds of oppositions.”

For the Trust the arguments against classification and positive preservation action are that: street art is not intended to last; exposure to the elements and the accessible, more destructive materials (from a conservation perspective) of production mean that street art has an increased timeline for decay and deterioration; as with the Keith Haring mural in Collingwood, fugitive pigments are at particular risk in natural UV and will quickly fade; due to the nature of the expression, it has proven difficult to prevent later street art obscuring the significant examples; it may be attached to an insignificant building proposed to be demolished, or the owner, or a future owner of the site, may not wish the graffiti to remain.

The arguments for preservation action include that: it may have social significance as community expression and public means of political and contemporary debate; it has aesthetic significance; it is covered by few controls and preservation of significant sites on the fringe of protection has traditionally been the purview of the Trust.

Eckett says: “While it would be inappropriate to attempt to classify works, we can advocate for better documentation of street art in Victoria and, in this way, help avoid lamentable situations such as the case of the Banksy stencil that was unwittingly destroyed in Prahran”.

Header image: TigTab/Flickr

+ There are no comments

Add yours